Julius Drake: ‘Unlike me, Mahler’s songs never age’

door Julius Drake 29 apr. 2025 29 april 2025

During the Mahler Festival, pianist Julius Drake will perform all 52 of Mahler’s songs, together with eight of his favourite vocalists. What makes these songs so special? The pianist on Mahler’s ‘mini masterpieces’.

Mahler’s songs are masterpieces of the repertoire, ranking alongside the great songs of Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Strauss and Wolf. But in one way they differ: many of them Mahler later rewrote for voice and full orchestra. These have become so famous in their gloriously colourful and characteristic orchestrations that sometimes the original versions were left in the shade, the overlooked sisters.

The truth is that the songs in their piano versions are marvels among Mahler’s compositions, miniatures as expressive and finely crafted as the famous symphonies are visceral and overwhelming.

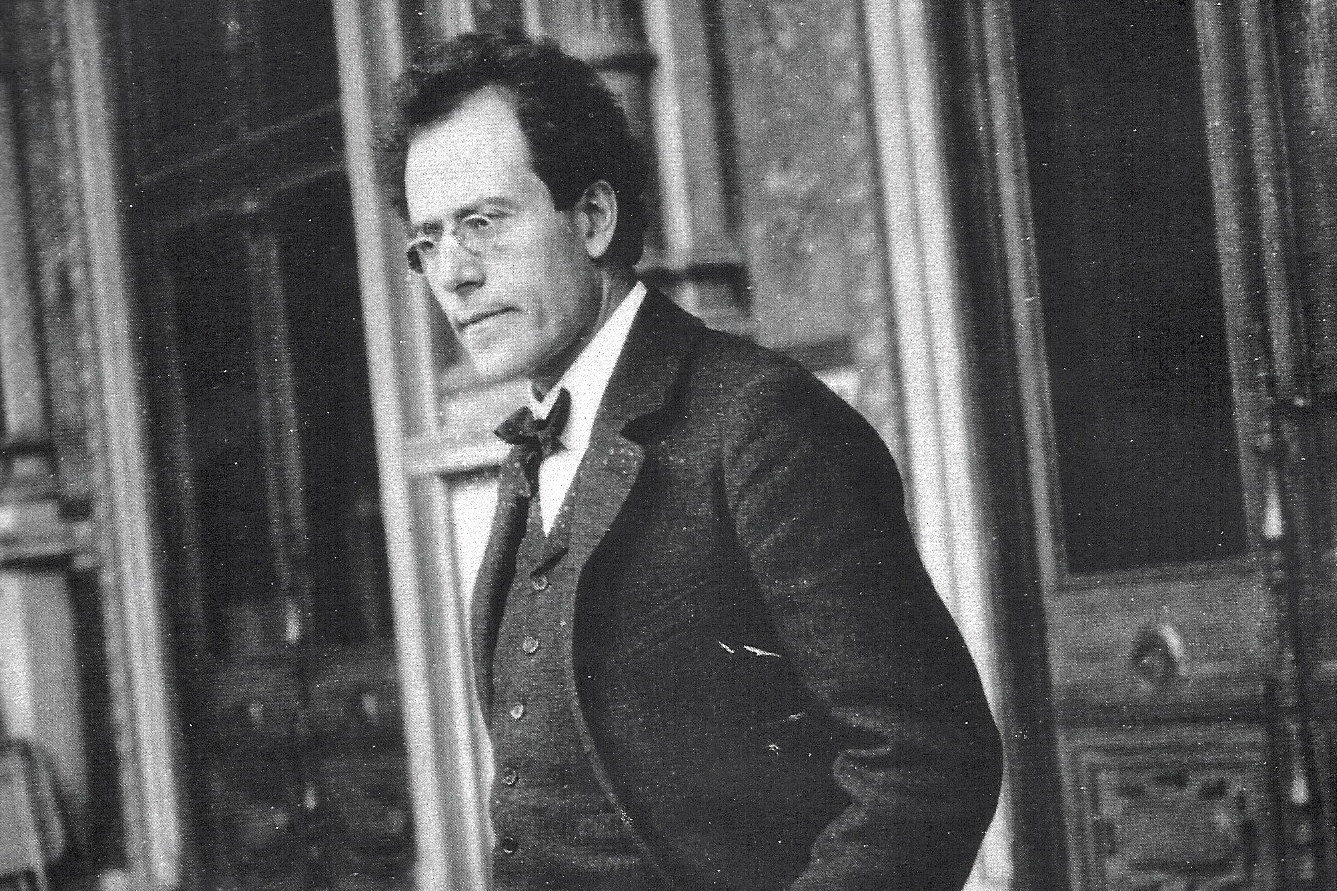

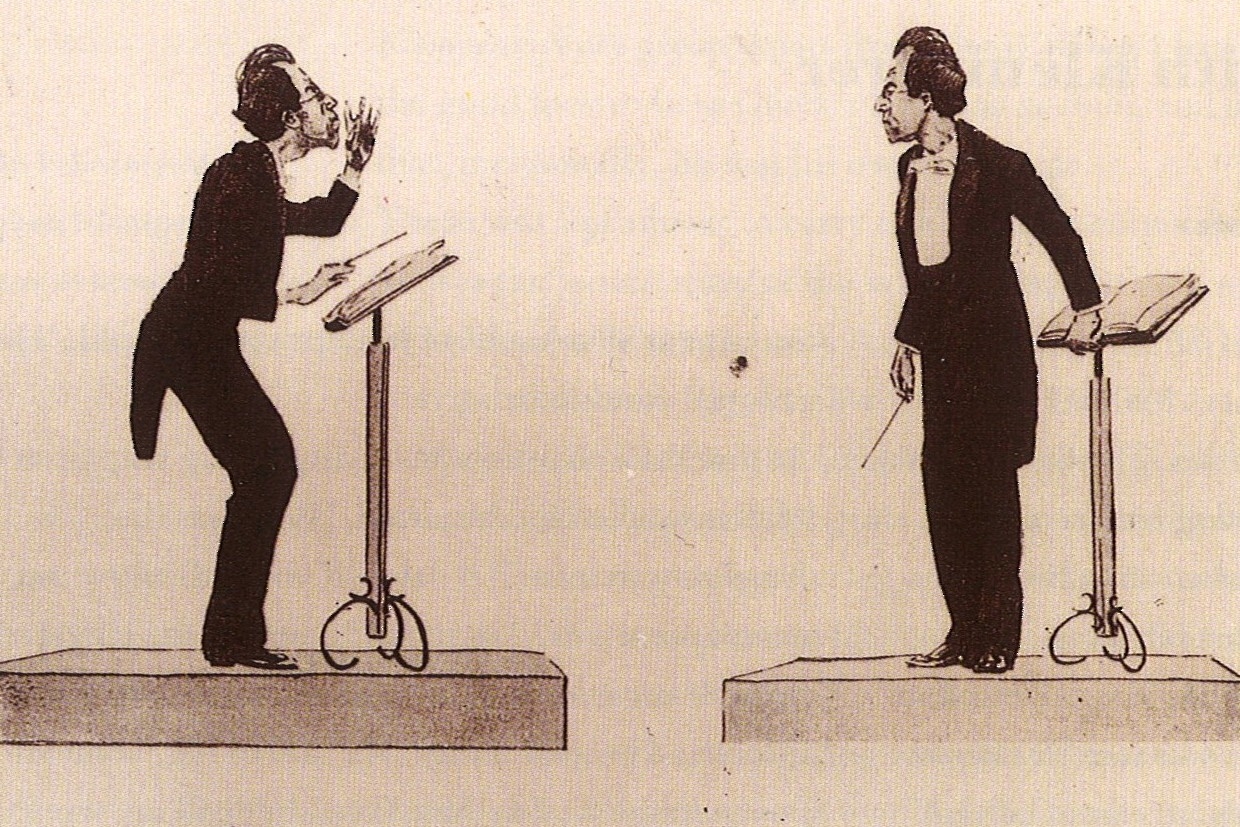

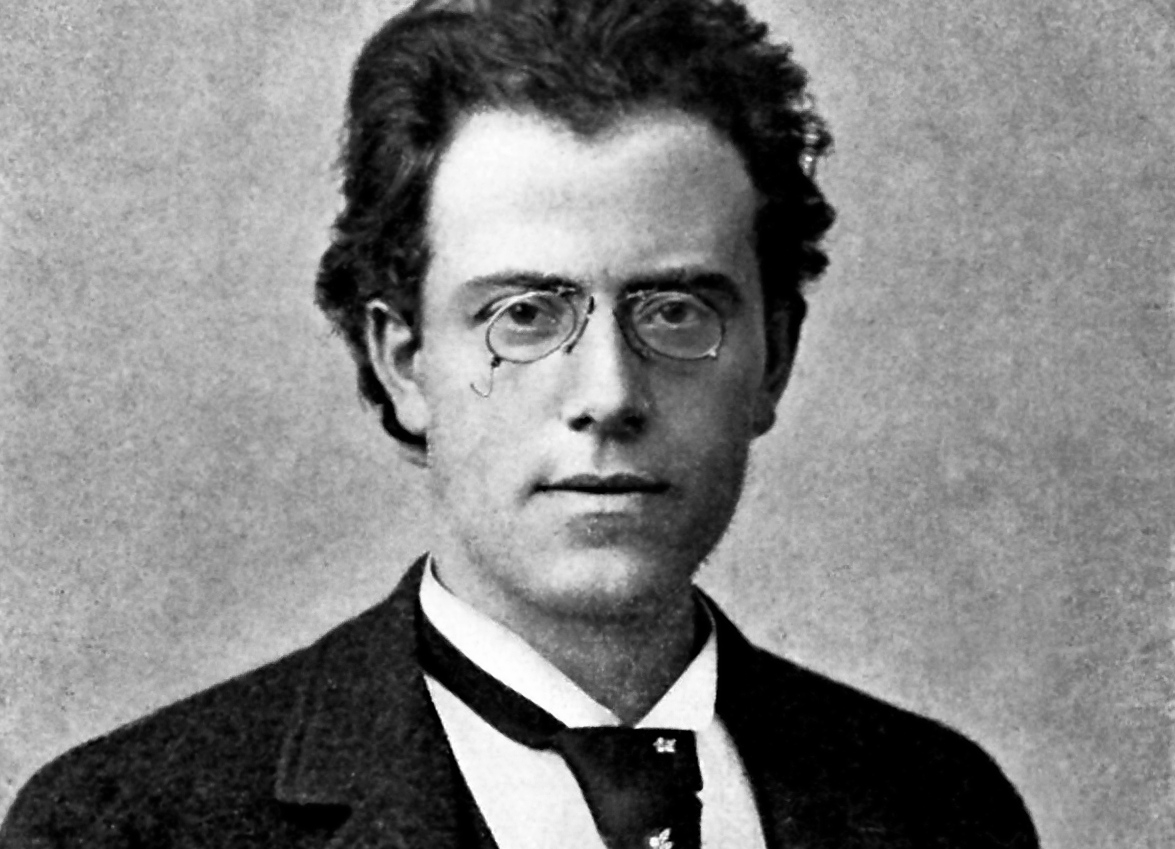

Mahler was much more celebrated in his lifetime as a conductor and music director than as a composer. As his career progressed, he had a series of demanding appointments: Director of Opera at the Budapest State Opera, then at the Hamburg State Opera and finally at the most prestigious of them all, the Vienna State Opera. Composing was restricted to his summer holiday and he would spend the summers beside the idyllic Corinthian lakes, not far from where he was born. He rented small lakeside huts to which he would retire to write, and as he always wrote at the keyboard, he had an upright piano installed in the hut. You can still visit the one near his villa on the Wörthersee, where he wrote his Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies.

When Mahler was studying at the Vienna Conservatoire, he won prizes for his piano playing. It is clear that the piano was an essential means for his own musical expression, and all his songs have beautifully written piano parts. Song composers tend to be pianists, sometimes brilliant virtuosos such as Brahms, or failed virtuosos such as Schumann, or simply not virtuosos at all such as Schubert, but all essentially writing their songs from the perspective of their beloved piano.

For me the Kindertotenlieder are Mahler's greatest achievement in song

Unlike Schumann, Schubert or Brahms, Mahler wasn’t forever searching for musical inspiration in volumes of poetry. Indeed, his very earliest songs were often settings of his own texts. Im Lenz, Winterlied, Hans und Grete, and the miraculous short song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, were all settings of his own poems.

It wasn’t much later, however, that he discovered his greatest resource for song inspiration, the large collection of folk poetry compiled in the early nineteenth century by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano, Des Knaben Wunderhorn. In the very first publication of his music, there were ten settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn for voice and piano. The texts included just one song of love and longing, the beautiful Nicht wiedersehen!. The rest was a mixture of high spirited ‘character’ songs, and songs that celebrated the beauty and joy of nature. Another kind of text that was to inspire Mahler throughout his life makes its first appearance in this collection: the poem set in, or around, the military barracks. Zu Straβburg auf der Schanz is haunting, and the precursor for later masterpieces such as Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen, Der Tambourg’sell and Revelge as well as the dramatic marches found later in the Third and Sixth Symphonies.

Finally we come to Das Lied von der Erde, which he called his ‘vocal symphony’. It was only recently confirmed that Mahler wrote a version for two voices and piano. Unlike his other vocal works, Mahler always intended Das Lied von der Erde, written between 1908 and 1909, at a time of great personal crisis, to be for two voices and full orchestra. Indeed, he wrote that the only reason he wouldn’t call the work his Ninth Symphony was out of superstition – Beethoven, Bruckner and Dvořák had all died after (or while) writing their own ninth symphonies. Mahler, who had just completed his Eighth, was painfully aware that his health was failing.

The poems that inspired him for Das Lied von der Erde were from Die chinesische Flöte, versions by Hans Bethge of ancient Chinese poetry. Mahler was captivated by their simple, timeless quality. In this one case, we don’t know for sure whether the piano version came before the orchestrated version, or after. The two versions differ in some places, enough to have been given separate opus numbers in the catalogue of Mahler’s works. My own feeling, after playing and studying it at the piano, is that Mahler wrote the orchestral version first – the piano version doesn’t have the same finesse or pianistic quality that his other songs have. Nevertheless, it is an enormous privilege to have Mahler’s own version for piano and voices of this seminal masterpiece, often considered his greatest work. I have spent forty years studying and playing these songs and, unlike me (!), they never age. They range wide, from comic songs to serious metaphysical meditations, from touching love songs to sublime reflections on life’s meaning, from simple folksong-like miniatures to entire song cycles. Along the way, I have felt Mahler the pianist by my side, encouraging me to find the endless colours and subtlety within his piano writing, and to give life to these amazing songs.

Mahler’s songs are masterpieces of the repertoire, ranking alongside the great songs of Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Strauss and Wolf. But in one way they differ: many of them Mahler later rewrote for voice and full orchestra. These have become so famous in their gloriously colourful and characteristic orchestrations that sometimes the original versions were left in the shade, the overlooked sisters.

The truth is that the songs in their piano versions are marvels among Mahler’s compositions, miniatures as expressive and finely crafted as the famous symphonies are visceral and overwhelming.

Mahler was much more celebrated in his lifetime as a conductor and music director than as a composer. As his career progressed, he had a series of demanding appointments: Director of Opera at the Budapest State Opera, then at the Hamburg State Opera and finally at the most prestigious of them all, the Vienna State Opera. Composing was restricted to his summer holiday and he would spend the summers beside the idyllic Corinthian lakes, not far from where he was born. He rented small lakeside huts to which he would retire to write, and as he always wrote at the keyboard, he had an upright piano installed in the hut. You can still visit the one near his villa on the Wörthersee, where he wrote his Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies.

When Mahler was studying at the Vienna Conservatoire, he won prizes for his piano playing. It is clear that the piano was an essential means for his own musical expression, and all his songs have beautifully written piano parts. Song composers tend to be pianists, sometimes brilliant virtuosos such as Brahms, or failed virtuosos such as Schumann, or simply not virtuosos at all such as Schubert, but all essentially writing their songs from the perspective of their beloved piano.

For me the Kindertotenlieder are Mahler's greatest achievement in song

Unlike Schumann, Schubert or Brahms, Mahler wasn’t forever searching for musical inspiration in volumes of poetry. Indeed, his very earliest songs were often settings of his own texts. Im Lenz, Winterlied, Hans und Grete, and the miraculous short song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, were all settings of his own poems.

It wasn’t much later, however, that he discovered his greatest resource for song inspiration, the large collection of folk poetry compiled in the early nineteenth century by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano, Des Knaben Wunderhorn. In the very first publication of his music, there were ten settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn for voice and piano. The texts included just one song of love and longing, the beautiful Nicht wiedersehen!. The rest was a mixture of high spirited ‘character’ songs, and songs that celebrated the beauty and joy of nature. Another kind of text that was to inspire Mahler throughout his life makes its first appearance in this collection: the poem set in, or around, the military barracks. Zu Straβburg auf der Schanz is haunting, and the precursor for later masterpieces such as Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen, Der Tambourg’sell and Revelge as well as the dramatic marches found later in the Third and Sixth Symphonies.

Finally we come to Das Lied von der Erde, which he called his ‘vocal symphony’. It was only recently confirmed that Mahler wrote a version for two voices and piano. Unlike his other vocal works, Mahler always intended Das Lied von der Erde, written between 1908 and 1909, at a time of great personal crisis, to be for two voices and full orchestra. Indeed, he wrote that the only reason he wouldn’t call the work his Ninth Symphony was out of superstition – Beethoven, Bruckner and Dvořák had all died after (or while) writing their own ninth symphonies. Mahler, who had just completed his Eighth, was painfully aware that his health was failing.

The poems that inspired him for Das Lied von der Erde were from Die chinesische Flöte, versions by Hans Bethge of ancient Chinese poetry. Mahler was captivated by their simple, timeless quality. In this one case, we don’t know for sure whether the piano version came before the orchestrated version, or after. The two versions differ in some places, enough to have been given separate opus numbers in the catalogue of Mahler’s works. My own feeling, after playing and studying it at the piano, is that Mahler wrote the orchestral version first – the piano version doesn’t have the same finesse or pianistic quality that his other songs have. Nevertheless, it is an enormous privilege to have Mahler’s own version for piano and voices of this seminal masterpiece, often considered his greatest work. I have spent forty years studying and playing these songs and, unlike me (!), they never age. They range wide, from comic songs to serious metaphysical meditations, from touching love songs to sublime reflections on life’s meaning, from simple folksong-like miniatures to entire song cycles. Along the way, I have felt Mahler the pianist by my side, encouraging me to find the endless colours and subtlety within his piano writing, and to give life to these amazing songs.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn was the inspiration for fifteen more songs written by Mahler for voice and piano, but this time, he also orchestrated them. The title he gave when they were published was Lieder, Humoresken und Balladen. Clearly, the songs he wrote were inextricably linked to the symphonies that were also germinating in his mind. One of the early songs from Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, for instance, was incorporated into his First Symphony. In the Symphonies Nos. 2, 3 and 4, singers would join the orchestra and the song and words would be included, too. Urlicht and Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt both feature in the Second Symphony and Es sungen drei Engel and Ablösung im Sommer in the Thirds. The divine Das himmlische Leben is orchestrated as the last movement of the Fourth Symphony. All are song settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

In June of 1901 Mahler suffered a serious haemorrhage that required emergency treatment and seven weeks of recuperation. Mahler spent those weeks at the villa he had recently bought near Maiernigg, on the Wörthersee, and it seems that it was probably then that he read the poetry of Friedrich Rückert for the first time. He was inspired to set ten of these poems to music; five became the Rückert-Lieder and five the Kindertotenlieder. As he later wrote: ‘After Des Knaben Wunderhorn I could not compose anything but Rückert — this is lyric poetry from the source, all else is lyric poetry of a derivative sort.’

Rückert’s poetry inspired some of Mahler’s greatest music. The exquisite delicacy of the vocal and piano writing in Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft and Liebst du um Schönheit and the searing intensity of Um Mitternacht are overwhelming. In Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen Mahler takes us to a place of utter peace where life’s pain can no longer touch us, a vision of another world that has rarely been matched.

Mahler was the father of two daughters, and the poems that Rückert wrote after the death of his own children from scarlet fever, profoundly moved Mahler. Of the 428 poems written by Rückert to exorcise his grief, Mahler chose five for his song cycle, Kindertotenlieder. The depth of the pain and loss that they manage to express is devastating and heartbreakingly beautiful. For me they are his greatest achievement in song.

Who is Julius Drake?

Julius Drake enjoys an international reputation as one of the finest collaborative pianists. He regularly performs with many of the world’s leading singers, both on stage and in the recording studio. His passion for song has often led to invitations to curate recital series, including for the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Wigmore Hall in London, and the BBC. The British pianist teaches song accompaniment at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Graz, Austria. In December 2022, Julius Drake was awarded the Concertgebouw Medal.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn was the inspiration for fifteen more songs written by Mahler for voice and piano, but this time, he also orchestrated them. The title he gave when they were published was Lieder, Humoresken und Balladen. Clearly, the songs he wrote were inextricably linked to the symphonies that were also germinating in his mind. One of the early songs from Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, for instance, was incorporated into his First Symphony. In the Symphonies Nos. 2, 3 and 4, singers would join the orchestra and the song and words would be included, too. Urlicht and Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt both feature in the Second Symphony and Es sungen drei Engel and Ablösung im Sommer in the Thirds. The divine Das himmlische Leben is orchestrated as the last movement of the Fourth Symphony. All are song settings from Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

In June of 1901 Mahler suffered a serious haemorrhage that required emergency treatment and seven weeks of recuperation. Mahler spent those weeks at the villa he had recently bought near Maiernigg, on the Wörthersee, and it seems that it was probably then that he read the poetry of Friedrich Rückert for the first time. He was inspired to set ten of these poems to music; five became the Rückert-Lieder and five the Kindertotenlieder. As he later wrote: ‘After Des Knaben Wunderhorn I could not compose anything but Rückert — this is lyric poetry from the source, all else is lyric poetry of a derivative sort.’

Rückert’s poetry inspired some of Mahler’s greatest music. The exquisite delicacy of the vocal and piano writing in Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft and Liebst du um Schönheit and the searing intensity of Um Mitternacht are overwhelming. In Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen Mahler takes us to a place of utter peace where life’s pain can no longer touch us, a vision of another world that has rarely been matched.

Mahler was the father of two daughters, and the poems that Rückert wrote after the death of his own children from scarlet fever, profoundly moved Mahler. Of the 428 poems written by Rückert to exorcise his grief, Mahler chose five for his song cycle, Kindertotenlieder. The depth of the pain and loss that they manage to express is devastating and heartbreakingly beautiful. For me they are his greatest achievement in song.

Who is Julius Drake?

Julius Drake enjoys an international reputation as one of the finest collaborative pianists. He regularly performs with many of the world’s leading singers, both on stage and in the recording studio. His passion for song has often led to invitations to curate recital series, including for the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Wigmore Hall in London, and the BBC. The British pianist teaches song accompaniment at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Graz, Austria. In December 2022, Julius Drake was awarded the Concertgebouw Medal.